…How to See the Real Cost of a Mortgage

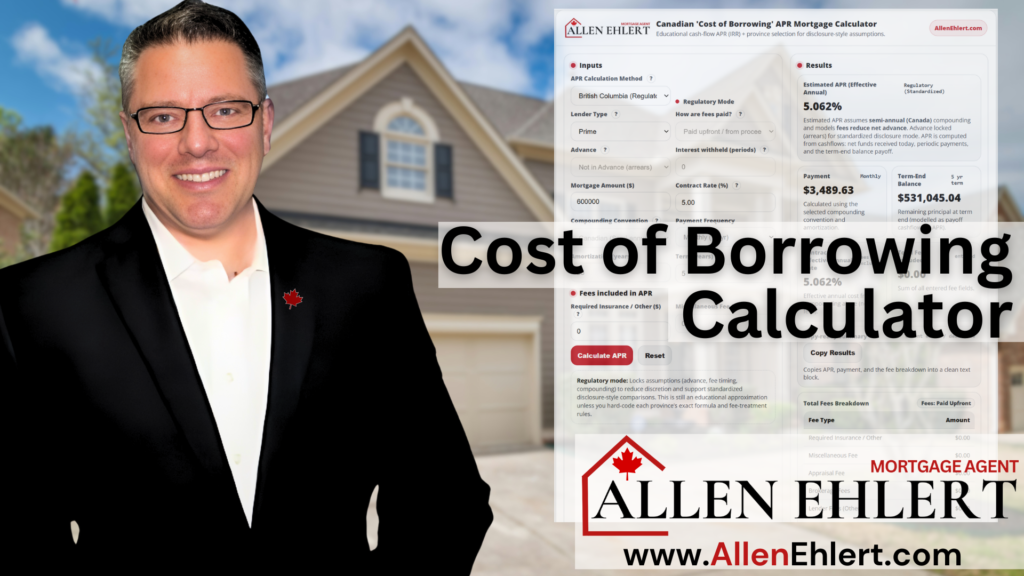

Annual Percentage Rate (APR) is one of those mortgage concepts that everyone’s heard of but few people truly understand. Most borrowers focus on the interest rate because it’s simple, familiar, and easy to compare. But APR — the Annual Percentage Rate — is where the real truth lives, not in the advertised rate—which is NOT what you pay. APR exists to answer a more important question: what does this mortgage actually cost once everything required is accounted for?

Across Canada, regulators may use different statutes and slightly different wording, but the underlying logic of APR is remarkably consistent. Once you understand the core principles behind it, APR stops being mysterious and starts acting like a spotlight. It shows you when a deal is clean — and when something is quietly making it more expensive than it looks.

Here’s how I’ve structured this article:

The Purpose Test (Cost to Access Credit)

Who Receives the Fee Doesn’t Matter

How the Fee Is Paid Doesn’t Matter

Financing a Fee Automatically Triggers Inclusion

Disclosure Alone Is Not Enough

Timing Changes APR — Inclusion Never Does

1. The Necessity Test

If you must pay a fee to obtain the mortgage, that fee belongs in APR. This is the cornerstone principle.

APR doesn’t care whether a fee is common, customary, or “industry standard.” If the mortgage cannot exist without that fee being paid, it’s part of the cost of borrowing. Administrative fees, lender setup fees, underwriting fees, and mandatory appraisals all fall squarely into this category.

Example:

A lender charges you a $1,200 administration fee on every mortgage they approve. You have no way around it. That fee must be included in APR.

In practice:

Mortgage agents and Financial Planners can use this principle when reviewing commitments with clients. If a fee is unavoidable, it should influence which mortgage is truly cheaper — not just which one has the nicer-looking rate.

2. The Borrower Choice Test

APR hinges on whether the borrower has a real choice.

If you can reasonably obtain the mortgage without paying a particular fee, that fee is typically excluded from APR. If there’s no meaningful choice, the fee is included.

Example:

Title insurance is required by some lenders but optional with others. If a lender says, “You must purchase title insurance to get this mortgage,” it belongs in APR. If the borrower can choose between title insurance or a lawyer’s opinion on title, and picks title insurance voluntarily, it does not.

In practice:

Clients often assume all closing costs are treated the same. Realtors who understand this principle can help clients distinguish between optional extras and costs that genuinely affect borrowing comparisons.

3. The Purpose Test (Cost to Access Credit)

APR includes fees that exist because credit is being advanced.

If the fee exists to approve, structure, fund, register, or secure the mortgage, it’s a borrowing cost. If it exists because you are buying or owning property, it usually isn’t.

Example:

An appraisal required by the lender is included in APR. A home inspection chosen by the buyer for peace of mind is not.

In practice:

This principle helps clients understand why some “real estate costs” affect APR while others don’t — even if both show up on the closing statement.

4. Who Receives the Fee Doesn’t Matter

APR doesn’t care who gets paid.

Whether the money goes to the lender, the brokerage, a lawyer, an appraiser, or an insurer is irrelevant. What matters is why the fee is being paid.

Example:

A brokerage fee paid directly by you is included in APR. A brokerage commission paid by the lender but reimbursed by you is also included in APR.

In practice:

This principle trips up a lot of files. Realtors and clients sometimes assume that if a fee isn’t paid to the lender, it doesn’t affect borrowing cost. APR exists to eliminate that blind spot.

5. How the Fee Is Paid Doesn’t Matter

APR is indifferent to payment mechanics.

Fees paid upfront, deducted from proceeds, paid outside the mortgage, or rolled into the loan all get treated the same from an inclusion standpoint.

Example:

A $5,000 lender fee paid in cash still increases APR. The same $5,000 fee financed into the mortgage also increases APR — just in a different way.

In practice:

Clients often feel better financing fees because the payment impact seems small. APR reveals the longer-term cost of that decision.

6. Financing a Fee Automatically Triggers Inclusion

If a fee is financed, inclusion in APR is unavoidable.

Financed fees increase the loan balance, attract interest, and are repaid over time. From a regulatory perspective, they are unequivocally part of the cost of borrowing.

Example:

A private lender finances a $10,000 commitment fee into the mortgage. You now pay interest on that $10,000. It must be included in APR.

In practice:

This is especially relevant in alternative and private lending. Realtors working with clients in these spaces should expect APR to move materially when fees are financed.

7. Disclosure Alone Is Not Enough

Listing a fee is not the same as including it in APR.

Regulators routinely find files where fees were disclosed transparently but omitted from the APR calculation. That is still non-compliant.

Example:

A commitment letter clearly lists a $2,500 brokerage fee, but the APR is calculated using interest only. That APR is wrong.

In practice:

Clients often assume that “as long as it’s written down, it’s fine.” APR exists precisely because disclosure without math can still mislead.

8. Materiality Is Irrelevant

There is no “too small to matter” rule.

A $300 fee and a $30,000 fee are treated the same conceptually. If the fee is required, it belongs in APR.

Example:

A $350 document preparation fee required by the lender must be included, even if it seems insignificant compared to the loan size.

In practice:

This principle protects borrowers from death-by-a-thousand-cuts pricing, where lots of small fees quietly inflate the true cost.

9. Timing Changes APR — Inclusion Never Does

When a fee is paid affects how much APR changes, but not whether the fee is included.

Fees paid earlier have a larger impact on APR than fees paid later, because they reduce net funds advanced.

Example:

Two mortgages have identical fees, but one charges them upfront and the other collects them at renewal. The upfront-fee mortgage will show a higher APR.

In practice:

This is where APR becomes especially useful for short-term, interest-in-advance, or private mortgages — situations where timing matters a lot.

10. When in Doubt, Include

This is the safest professional rule.

Regulators penalize omission far more than conservative inclusion. If there’s genuine uncertainty about whether a fee belongs in APR, inclusion is almost always the safer choice.

Example:

A lender introduces a new “review fee” that doesn’t fit neatly into a category. Including it in APR avoids risk and ensures transparency.

In practice:

This principle keeps brokerages on solid footing and protects clients from unpleasant surprises later.

A Short Story That Brings It Together

Consider a buyer choosing between two five-year mortgages. Both advertise the same rate. One has no fees. The other has a mix of lender, brokerage, and appraisal fees totaling $8,000.

The payments look identical. The rate looks identical. But APR tells a different story — and once the buyer sees that difference, the decision becomes obvious.

That’s APR doing exactly what it was designed to do.

Allen’s Final Thoughts

APR isn’t there to confuse you — it’s there to protect you. It forces the mortgage conversation to move beyond headline rates and into real-world costs, where decisions actually matter. When you understand the principles behind APR, you’re no longer guessing which mortgage is cheaper. You know.

As a mortgage agent, my role isn’t just to quote rates. It’s to interpret structure, fees, timing, and risk — and to translate all of that into something you can confidently act on. I help clients and realtors spot when a deal is clean, when it’s quietly expensive, and when the trade-offs are actually worth it.

If APR feels complicated, that’s normal. The goal isn’t for you to calculate it — it’s for you to understand what it’s telling you. That’s where I come in.